A Prehistoric Cultural and Religious Center

Kincaid Mounds, in Southern Illinois

by John E. Schwegman

The arrival of corn and intensive corn cultivation in the eastern United States over 1000 years ago transformed the dominant native American groups there from mobile hunters, gatherers, and gardeners able to support only small villages to sedentary farmers able to support larger towns and even small cities. This transformation gave rise to the people or culture we call “Mississippian” about 900 AD.

Thanks to agriculture and the stable and more abundant food supply it provided, the Mississippian people were able to devote time to construction of communal facilities such as platform mounds, defensive walls or stockades, and temples. They lived under a form of leadership called a complex chiefdom led by a male chief and his family who exerted civil control over the community and priests who held religious authority over them. The Chief inherited his position from his mother, who was the eldest sister of the previous Chief.

Some time around 1,050 AD, Mississippian leaders and their followers arrived in what is now eastern Massac and southern Pope Counties of Illinois and established scattered farming villages and a cultural center. Their cultural center is what we call Kincaid Mounds today, named after early European owners of the site. Judging from their cultural traits, these early Kincaid people came from a Mississippian area to the southeast along either the Cumberland or Tennessee Rivers. This founding group probably split away from another Chiefdom after a strong leader and his family arose and attracted a following.

The region they selected was a wide section of the floodplain of the Ohio River near the mouths of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers now known as the Black Bottom. It was a forested area with rich alluvial soils whose fertility was replenished by almost annual overflow by the Ohio. The specific site they chose for their cultural center was a high ridge bordering the north side of Avery Lake and about a mile north of the present day Ohio River. Its high elevation reduced the frequency of flooding and made it suitable for a ceremonial and administrative center. These people also occupied the surrounding bottomlands where they lived in many small farming villages, or farmsteads, of one or two families located between the present-day towns of Hamletsburg, IL and Brookport, IL. Kincaid is located near the center of this agricultural production area.

The average temperature of the climate at the time of the founding of Kincaid was about 5 degrees warmer than today. This was during what climatologists call the “Medieval Warm Period” which lasted from AD 800 to AD1200. Climate cooling after this time, culminated in what climatologists call the “Little Ice Age” about AD 1350 when temperatures were colder than today. This colder climate may have played a role in eventual abandonment of Kincaid about AD1400.

Most of what we know about Kincaid comes from the extensive archaeological excavation of the site and its surrounding territory by the University of Chicago from 1934 through 1944 and work by Southern Illinois University in more recent times (see Research Section of this web site).The results of the Chicago work are compiled in the volume “Kincaid, a Prehistoric Illinois Metropolis” by Fay-Cooper Cole and others published by the University of Chicago Press in 1951. When the carbon 14 method of dating organic material was developed some years later, wood samples from Kincaid were dated by this process. These samples provide a more definitive time frame for the period of occupation of Kincaid than was available to Cole. Scientists from Southern Illinois University at Carbondale did salvage excavations in the late 1960s when the Massac County portion of the banks above Avery Lake were leveled by a farmer to create a small crop field. They also mapped the location of the outlying small farming villages and excavated several of them at that time.

In recent years SIU archaeologists and students have returned to Kincaid with annual summer excavations and an intensive effort to map the site with new technologies (primarily magnetometry) that allow viewing the locations of structures and features without the need to dig. My son and I have contributed to this high tech survey, helping with the SIU project on the public land and adding to it by mapping on adjacent private land to the north and east.

Magnetometry reveals cultural features because of the change in soil magnetism brought on by soil disturbance and alteration. Topsoil is high in magnetism, as is trash that is high in organic material. When these materials are used to fill wall trenches or pits into less magnetic subsoil the pits and walls show up sharply. Burning of soil alters its magnetism as does compacting soil. Thus fire hearths and burned structures show up well as do compacted foot paths between houses etc.

All of these efforts have added to our knowledge of the site and its people. Excavation by SIU has confirmed that the palisade was reconstructed several times and that more low mounds exist at the site than were previously recognized. The subsurface survey confirmed the exact location of the palisade and discovered many previously unknown structures. Another finding was that while rectangular structures prevail, circular structures are more common than previously known. My magnetometry on Mound 8 revealed the outline of a circular structure 22 meters (72 feet) in diameter. If excavation reveals that it was a roofed structure, it will be one of the largest known such structures in the United States.

Information on beliefs and social structure of the Mississippians comes mostly from historic accounts of the Mississippian villages encountered by the De Soto expedition of 1539 to 1543 and the French descriptions of the Natchez Indians near early New Orleans. The excavations and research at large Mississippian centers like Cahokia near Collinsville, Illinois, the Moundville Site at Moundville, Alabama, and many other sites including Kincaid have added much information as well. Even with these historic accounts and archaeological research, we will probably never know the details of the social structure and daily lives of the Kincaid people. However, this information allows us to speculate on what might have been.

The site of Kincaid Mounds was a large Early Woodland village over 2000 years ago and was occupied by the Late Woodland Culture just prior to the arrival of the Mississippian people. Whether the newly arrived Mississippians displaced the local Late Woodland “Lewis” Indians who previously lived there is unknown. They may have abandoned the site before the arrival of the corn farmers. However, some scholars believe that many local woodland peoples joined the Mississippians when they moved into a new area. Their corn economy offered the woodland people an easier life and more dependable food supply. At any rate, archaeologists find the remains of a late woodland village immediately beneath the earliest remnants of Kincaid.

The first Mississippian people at the Kincaid site made a low, square mound or platform of earth just 3 feet high at the site of Mound 7. This mound is next to the present road just west of the observation area. Upon this they erected a building that may have served as the seat of authority over this initial community.

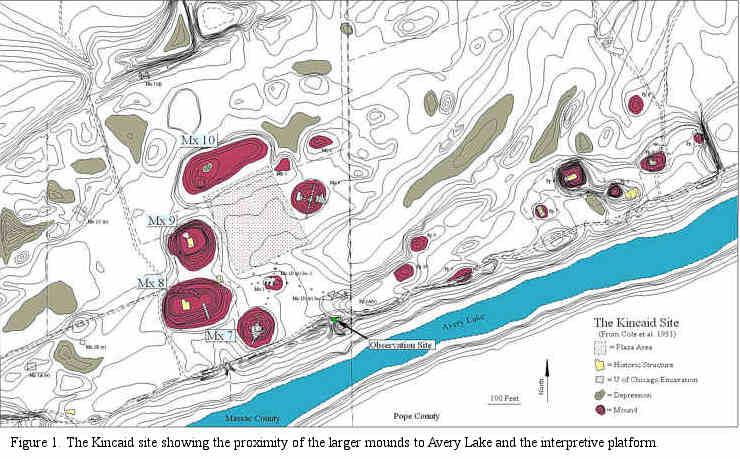

During the next 300 years these people added to this first structure until a total of 19 flat-topped earth mounds and several smaller platforms were constructed. It is estimated that these earthworks consist of 90,000 cubic meters of soil that was dug up with stone hoes and spades and carried up on the mounds in baskets. In terms of the volume of earth moved, Kincaid ranks about 6th among all of the prehistoric Mississippian sites. With 11 major mounds, it is 5th in the number of these mounds. At its height, the intensively occupied area of Kincaid stretched for a distance of three-quarters of a mile along Avery Lake. Figure 1 shows the site layout.

At least eight of these mounds survive to this day in a condition that the average observer would recognize as man made earth works. Some of the smaller mounds have been farmed over for years and appear today as high points in crop fields. The most notable mounds are in Massac County and can be viewed from an observation and interpretive platform (Figure 2) adjacent to Kincaid Mounds Road. Directions on reaching the site are given at the end of this article.

The Massac County part of the site is owned by the Illinois State Historic Preservation Agency and is managed by a local Kincaid Mounds Support Organization under contract with the State. At present the tillable land is managed by no-till cropping and the mounds have been cleared of trees and are planted to native prairie grasses. An interpretive platform and site overlook has been developed by the Support Organization with a grant from the Ohio River Scenic Byway and with the cooperation of Massac County government. The Pope County portion of the site and some of its north edge in Massac County are privately owned.

Features easily visible today are the west or largest mound group in Massac County and smaller mounds extending eastward into Pope County. The larger mounds in Massac County partially encircle an open, level area that served as a plaza or public quarter where ceremonies were held and games were played. A low linear ridge in the edge of the timber north of this mound group marks the location of a protective wall or palisade that encircled the site. Just north of this palisade are large borrow pits where material was excavated to make the mounds. A raised causeway crosses this pit and piles of excavated material, ready for transport to the mounds, can be seen. Back within the palisade, some raised areas are visible in village areas where houses were built one on top of another for centuries, or where low platforms to support structures were constructed.

University of Chicago archaeologists determined the chronology of construction of the earthworks and layout of the site. As mentioned earlier, the mound we now call Massac Mound #7 was the site of the very first Mississippian mound at Kincaid. This 3 foot high platform was later enlarged to a square platform mound some 15 feet in height topped by structures. During this period the primary village occupied the area to the north and east of this mound. The area north of this village later became the plaza.

At this point in time a major Ohio River flood occurred that inundated the entire site except for the lone mound. Gravel and white sand was deposited by the floodwaters throughout the village and on the sides of the mound. This flood exceeded in height any historic floods of the Ohio.

After this flood, a dramatic change took place at Kincaid. The old village was cleared away, a large plaza was established, and construction of three new mounds bordering this plaza on the west and north was begun. Massac Mound #7 was also raised to a new higher level. We may never know what triggered this abrupt change, but similar events happened at Cahokia and Moundville. In these cases the development followed the emergence of strong central political control and the immigration of people from small farming villages to the developing seat of power. This is probably what happened at Kincaid as either a new leader arose or a new religious order or concept spread into the area. This major construction phase at Kincaid took place in what is known as Kincaid’s Middle Component and what is called elsewhere the Classic Mississippian period.

Many of the new mounds began as lower platforms that were lived on or utilized for temples and then added to over the years. But the major mound of Kincaid, Massac Mound 8 (Mx 8), appears to be the result of one continuous construction effort over a relatively short period of time. This 30-foot high platform mound measures 300 feet east to west by 200 feet wide and covers an area of 2 acres. It supported the 72 foot diameter circular structure on its west end. It is remarkable today for its steep sides that indicate the “engineers” in charge of its construction understood how to overcome the natural tendency of earth piles to slump. It was constructed of mixed basket loads of different clays and soil that were stacked but not spread.

The Kincaid family built a home on top of this mound in 1876. A steep narrow roadway up its north side, used by the Kincaid family for access, may actually be an aboriginal ramp to the top. Only Massac Mound 10 is larger in area, and it is lower in stature. Figure 4 depicts Mounds 9 and 10 as they appear today from the top of mound 8. The plaza is to the right of Mound 9.

Massac Mound 10 is 485 feet long, 195 feet wide at the base and 20 feet high. The flat top is 100 feet wide. Excavation by University of Chicago shows that this mound was partially built by spreading the construction material rather than leaving the basket loads intact. This construction method appears to be inferior as it has led to slumping on the side of the mound that is visible on its north side.

After completion of the 20 foot tall part of Mound 10, a 100-foot diameter circular offset mound was added to its southwest corner. The offset overlooks the leveled part of the plaza and the site of a magnetometry feature that may be a ceremonial center or pole on the plaza. This offset rises 10 feet above the bulk of the mound and reaches the height of 30 feet above its base, the same height as Mound 8. The offset is flat to cup-shaped on top because it once had a rampart around its edge. It also had a spiral series of earthen steps to its top. One can only guess at its role in the social structure or administration of the community, but its proximity to the plaza may be significant.

One final mound of special note is the privately owned Pope County Mound 2, which lies at the extreme eastern end of the Kincaid site. It is the only wholly burial mound known at Kincaid and was excavated by the University of Chicago in 1936. Its lower levels hold burials in log tombs while those buried in the later upper level of the mound were buried in stone lined crypts. This mound has been farmed over for many years and now appears just as a low rise in the ground.

Another public work of note is the palisade. During the Middle Component construction boom, the entire Kincaid site was encircled by a palisade of upright logs or posts. It began at Avery Lake and arced out around all of the mounds and some of the residence areas before reaching down to Avery Lake again. The height of this wall is unknown, but it may only have been 6 or 7 feet tall. It was plastered with mud and had “guard houses” or bastions at intervals of about 100 feet. It was surely partially defensive but may also have functioned to mark the boundary of the ceremonial site and seat of authority. Southern Illinois University excavations show that it was rebuilt several times over the years. Palisades also encircled some of the temples on top of the pyramids. These were almost surely privacy fences since without a source of water, one could not long survive a siege on a mound.

Outside of the palisade wall, near the center of its north side, is a raised causeway or earthen walkway crossing a major borrow pit. It appears to be of prehistoric origin and may have functioned to bring mined soil into the site from this pit. It is also may have led to a gate in the wall at this point, but a magnetometry survey at this site does not clearly show an opening in the palisade here.

One final feature that probably stood at Kincaid was a tall monument pole. Several existed at Cahokia and De Soto describes them from Mississippian villages he visited in 1540. De Soto says the Indians hung scalps of vanquished foes from them. At Cahokia, a garbage pit near a monument pole was found to contain several legs and arms of different people indicating that various body parts were also hung from them. They obviously served as a public display of the power of the community or its leaders. If one existed at Kincaid, it was probably at the site of the magnetic anomaly in the northwest quadrant of the plaza. Excavation is needed to determine this.

The function of most structures that have been excavated seems to be as residences except for those on the larger mounds and smaller circular structures. The latter are thought to have been sweat lodges while those on the mounds are assumed to be religious or administrative in nature. The University of Chicago excavators of a structure on Mound 9 found a large hearth nearly 5 feet in diameter within it. They called it the “fire basin of a temple”. Priests of the Natchez were assigned to keep a perpetual fire going from year to year within a temple and one can only wonder if this is what was going on here. Active excavations of the large circular structure atop Mound 8 by Southern Illinois University may eventually reveal its function.

The structure on the largest privately owned mound at the east end of the site may have served as a “charnel house” for preparing the dead for burial since it is near the only known burial mound. Evidence from observation of surface cultural materials indicates that an artisan “workshop” area existed within the walls of Kincaid. Apparently this was for the production of special artifacts from fluorite and possibly other materials for the elite leaders.

The people who built and lived at Kincaid had no written language so we will probably never know what they called the site or for that matter what they called themselves. In 1540, the De Soto expedition learned from Indians of the southeast that a place near present day Kincaid was known to them as Tacaegani, but no one knows whether this was the name the Kincaid people used for the site. It is certainly more likely to be the Indian name than Kincaid is.

Archaeological evidence and historical accounts tell us the Mississippian peoples had a social structure in which males dominated and this was surely true at Kincaid. The Chief, Priests, and Shamen were men. Men belonged to clans with probably all of the political leaders or Chiefs at Kincaid belonging to one clan while the Priests may have belonged to another. At Cahokia near St. Louis, the leader was a member of the Sun Clan, but at present we do not know the clans of Kincaid. A great Chief (and possible founder) of the Mississippian city we call Cahokia was buried with servants and young women who were sacrificed, apparently to serve him in an after life. No such burial has been found as yet at Kincaid, but if its founder was a great charismatic leader, such a grave may await discovery.

We can be sure that the spiritual beliefs of the Kincaid people included belief in life after death as evidenced by pots and tools that they buried with some of their dead for use in the afterlife. Mississippian spiritual belief also included the existence of an under world that is home to monsters, night, and water creatures, and an upper world that is home to man and day creatures. Even though the under world is believed to harbor fearful creatures, it is also considered mother earth and the source of food. Underworld creatures at Kincaid are supernatural figures like the “dog” in Figure 5 as well as night and water creatures like owls, frogs, snakes, spiders, and turtles. The most famous of the underworld creatures was the Piasa Bird painted on the Mississippi River bluff at Alton, Illinois.

Men did the hunting and fishing and helped with the heavy work of clearing forest for farmland, building mounds, and constructing buildings. Men probably made most of the stone tools and did much of the trading with other communities. There was no standing army or police force, but in the event of warfare, the men did the fighting.

Women apparently did the farming and plant food gathering, cooking, gathering firewood, and rearing the children. Women probably made most of the ceramics or pottery and doubtless helped with mound building and building construction. They may have done the bulk of the spinning and weaving of fabric as well. Even though women were not community leaders, they were revered by the Mississippians as fertility symbols. Five god-like figurines carved of hard clay and found near Cahokia were all females and depicted the growth and production of plant food from the under world. Some archaeologists believe these figurines were gods of a fertility cult.

The diet of the Kincaid people was probably dominated by corn as studies show some Mississippian peoples got as much as 60% of their annual caloric intake from this one crop. While some of it may have been consumed as corn bread, the scarcity of mortars at Kincaid argues for most consumption as hominy and grits. Both of these latter dishes were invented by the Mississippians. Venison appears to have been their favorite meat.

It is remarkable what the Kincaid people accomplished so much with stone tools. Stone celts of granite and other fracture resistant igneous stone with a ground, sharpened edge were the main tool for cutting trees and firewood. Flaked chert (flint) adzes and chisels with sharp ground edges were used to work wood into useful objects. Flaked chert hoes, spades, and picks were used to dig and till the soil. Knives, projectile points, hide scrapers, drills and choppers were also made of flaked chert. Most projectile points (Figure 6) were relatively small arrowheads, as the recently introduced bow and arrow was available to them. Sandstone mortars and pestles (though not common at Kincaid) were used to pulverize seed, and hammer stones were used for cracking nuts

Chert came from a variety of sources from local creek and river gravel to widely known deposits of unique cherts. Chert occurring in slabs large enough to make hoes is rare and mostly came from deposits at Mill Creek in Union County, IL and from near Dover, TN. Igneous stone used for celts and maces came from greater distances, mostly from the north.

Ceremonial objects such as pipes, maces, and human effigies (Figure 7) were carved of stone. These artifacts were probably prestige objects owned only by the elite. Discoidals or discs of stone (Figure 8) functioned as rolled game stones in a contest called chunky where players tried to throw a spear where the stone would come to rest.

Bone, mostly of deer and turkey, was also an important tool-making material. Awls for puncturing hides for sewing were mostly of bone, and bone fishhooks have been found at Kincaid. Deer scapula or shoulder blades were sometimes fashioned into hoes for cultivating crops, and pieces of deer antler were fashioned into punches. Antler was also probably used in flaking flint tools. The moist, acidic soils at Kincaid make bone preservation poor, thus bone artifacts and human skeletal remains are rare here.

Pottery and other ceramic objects were very important at Kincaid. Their potters fashioned large jars and bowls for grain and food storage, pots for cooking, bottles for storing water, plates and cups for eating, and broad shallow pans for making salt by evaporation. They even made a cylindrical object with a large opening at one end and a small opening at the other that was apparently used to extract juice or fluids from fruit or other products. They colored some of their wares with red or black coatings and decorated some with impressed fabric and other incised designs, and with black and white and red and black surface designs. They added loop handles, lugs or protruding handles, and occasionally legs on their wares. The potters sometimes sculpted animal and human motifs to decorate their wares. Examples are a dish with a duck head attached to the rim and a water bottle with an owl head at its opening (Figure 9). In the latter case, water is poured from the owl’s mouth. The Kincaid people were very aware of wildlife and include wood ducks, owls, frogs, turtles, fish, and bear in their sculpting on pottery. They also include human faces.

They made many other objects of ceramic as well. These include most pipes for smoking, effigy rattles, human effigies (Figure 10), torch holders for a ceremonial temple, and spindles for spinning thread and cord. Pottery trowels used to smooth ceramic clay prior to firing were made of fired clay as well.

Apparently local clays were used to make pottery and other ceramics. To counter the tendency of these clays to crack during firing; burned, crushed mussel shell was added to the clay. This shell tempering of the clay apparently reduced breakage and provides an easily observed marker for Mississippian ceramics. The only Kincaid people who did not use shell tempering were the people who made the very first mound. These people added crushed pottery called grog to their clay rather than shell.

Fluorite crystals, shell, and cannel coal were fashioned into ornaments such as pendants, beads, and earplugs (Figure 11). Fluorite came from deposits just to the east of Kincaid, cannel coal came from river gravels or was traded from the east, and shell came from local river mussels or was traded from the Gulf of Mexico. Cannel coal is a fine grained coal composed mostly of pollen grains of the scale trees and ferns that make up the coal beds. Pollen grain coals are high in wax giving cannel coal objects their ability to be polished to a high shine.

Ear plugs were worn through the pierced ear lobes, and possibly lips, of men. Beads and pendants were strung and worn around the neck. A partial disc or gorget from Kincaid is of carved conch shell, whose material had come from the Gulf of Mexico. It is drilled for stringing and wearing around the neck. It depicts a man wearing a loin cloth or apron with a “spider” motif. This could indicate that one of the clans at Kincaid was the spider clan. An effigy of a human head of highly polished cannel coal is one of the most remarkable artifacts from Kincaid (Figure 12). It may have been strung and worn dangling from the ear.

Religious and clan articles were also fashioned from these materials. One disc of coal from Kincaid is carved to depict an “underworld creature”, a dog-like animal with upright ears (Figure 5). Effigies of owls carved from fluorite and cannel coal have also been found. A unique artifact in the form of a small statue appearing to be of a man with an owl head, carved of white aragonite, was reportedly found at the base of Mound 8 below the large circular structure. Clans may have been named for a variety of animals including the owl.

Fibers for weaving cloth, mats, fishnets, and baskets were probably all gathered from the wild. Fibers from common nettle, some milkweeds, basswood inner bark, and Indian hemp (dogbane) were probably used for cloth, with the latter especially used to make rope and cordage like bowstrings. Baskets may have been made from basswood bark and mats and baskets were often woven from split cane. These materials would be used for everything from clothing to building construction materials. Cane mats were used in house wall construction and as coverings for benches and beds. One burial in Pope Mound #2 was buried wearing a headdress of thin wooden fibers. Viburnum branches may have served as arrows, while the wood of choice for bows was probably red mulberry.

Cultivated crops included corn and tobacco, but other possible crops like squash and gourds can only be speculated on. They made pottery in the shape of gourds, so gourds were probably grown and used as containers and rattles. They also probably cultivated wild seed plants such as lamb’s quarters, amaranth, and sumpweed. Domesticated Lamb’s Quarter and squash seeds were found at a contemporaneous Mississippian site in Massac County.

Their houses were rectangular in shape and ranged from 9 X 12 feet up to 25 X 35 feet. The walls were built of a series of vertical posts placed in a trench to which horizontal poles were lashed to produce a lattice. Grasses and reeds were then lashed to both the inside and outside of the lattice and this grass layer was covered with mud plaster. The final stage of wall construction was covering it all with woven cane mats on the outside and thinner split cane mats on the inside. The finished walls were about one foot thick, very rigid and highly insulated for warmth in winter and coolness in summer. Rafters were then added atop the walls and joined with cross poles to form a lattice to which grasses were added to make a thatched roof. Joists were added to provide a ceiling and an attic where corn was stored. Interior furnishings included benches and beds along the walls and a central fire-basin. Some houses had interior posts and most had a central side door. Most houses and other buildings were oriented parallel to Avery Lake.

Most communal buildings and temples were larger, had gable construction of roofs, and had larger, stronger wall posts. The walls were thickened in the same manner as the houses, and the roofs were also of thatched grasses. Braided ropes were used to lash large beams together. These temples or ceremonial buildings stood on pyramids, and some had palisades or walls around them. Most were square or rectangular and not less than 40 feet long, but an exception was a circular structure 72 feet in diameter. The lack of trash in and around these larger structures indicates that they probably were not the homes of chiefs or priests but rather were sites where ceremonies were carried out. Excavations have also revealed smaller narrow buildings that may have served as corn cribs or for other unknown uses. Small circular huts with central fire pits and benches all around the outer wall are interpreted as sweat lodges or saunas.

The people who built Kincaid dressed in clothing of cloth woven from wild fibers and wore some of their hair up in a knot on top of the head or braided down the back. Women probably wore wrap-around skirts that reached to just above the knee, as the Cahokia women did. Shoes were probably of deer hide, but such material is poorly preserved at Kincaid and their presence must remain speculation. The men pierced their ears and wore earplugs of fluorite, ceramic and cannel coal. A few wore ear spools fashioned of cannel coal. Necklaces of beads made of rolled sheet copper, ceramic, fluorite, and shell have been found. A ring fashioned of polished bone is known, and pendants of stone and fluorite were worn around the neck. The abundance of polished stones that have apparently been used in rattles raises the possibility that Kincaid men, possibly just the elite, wore rattles at their knees or used gourd rattles in ceremonies. Ceramic effigy rattles with small clay beads and stones inside are also known.

The plaza was probably used as a game-court for chunky and other games, as a site for a pole monument to the power of Kincaid and for various ceremonies. Perhaps its most important use was for an annual “green corn ceremony” of renewal. We know of this ceremony from early historic accounts of Mississippians observed by De Soto. During late summer as corn was ripening in the fields, much as we have agricultural fairs, the local Mississippian peoples gathered at Kincaid. Priests conducted rituals involving different colored corn kernels around the monument pole. No new crop corn could be eaten before this ceremony was completed. The assembled citizens repaired homes, temples, and other buildings. Vermin-infested or deteriorated buildings were burned and rebuilt. Mounds might be added to and raised higher by those gathered including erecting new temples on them. Palisades might be erected or repaired as well. Perhaps the most remarkable “renewal” was the drinking of the “black drink” by the men of the community. This drink was concocted of a southern holly shrub (Ilex vomitoria) and caused the men to purge the contents of their digestive tract, thus renewing them for the year to come. This drug was probably traded for from other Mississippians living to the south.

By the year1500, the area including Kincaid, Cahokia, and the lower reaches of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers was empty of all significant cultural complexes. This region at this time is called the “vacant quarter” by archaeologists. Where the Kincaid people went is not known, but the shift to a colder climate, depletion of timber for fuel and construction materials, and the decline of central control may have all played a role. At any rate the Indians that had moved back into the area by the time of European arrival in the late 18th century had no idea who made the mounds.

To visit Kincaid Mounds, take the Unionville Road east from Route 45 at the north edge of Brookport. Go 6.25 miles (through Unionville) to the New Cut Road, then south on New Cut Road for 3.6 miles to the Kincaid Mounds Road. Drive east on the Kincaid Mounds Road for .6 of a mile to the observation and interpretation platform. When visiting the interpretive site try to imagine the tremendous activity that occurred on this plaza and surrounding mounds and villages on green corn ceremony day nearly a thousand years ago! Perhaps some day volunteers will reenact this and other ceremonies at Kincaid.

After leaving the observation area, one can proceed east along the road. You will soon enter the woods at the Pope County line. Keep looking on the left side of the road for additional privately owned mounds in the wooded area. The last notable mound has the remains of an old house on it. At this point turn around and retrace your route back west or continue on to the town of New Liberty where you can continue on to Golconda or return to Brookport.